Wala-fair in Logic Mar, The thirtieth day of Januar..

In this week we read about a neglected masterpiece, four Scottish Saints, one Angelic Doctor and much more! Welcome to the Coracle.

Ah me! How calm and deep

A Neglected Masterpiece by Peter Abelard

I was introduced to this hymn in its English translation when I was a student in Rome and long before I discovered the beauty of the Latin original, not to mention the bizarre career of its author, Peter Abelard. Our choirmaster was one Charlie Renfrew, a former Boy Scout and future auxiliary bishop in Glasgow. No doubt it was ‘under a spreading chestnut tree’ that he discovered a talent for singing choruses around the campfire with accompanying gestures and introduced this talent to the Scots College. Sadly, you will seldom hear this particular hymn sung today, with or without gestures, in spite of the fact that the words are set to a very beautiful melody. At all events, Charlie had an ear for good community singing and I am grateful to him for introducing me to this masterpiece.

At a distance of sixty years, I still don’t find it easy to put my finger on the precise reason for my enduring affection for it, whether in English translation or in the original Latin of Peter Abelard. It may simply be that it captures something of the spirit of those carefree days and youthful promise. With the passing years I now appreciate better that it treats of the ultimate promise of life and refuses to be satisfied with anything less. Our poem begins where life on earth ends and addresses what we now call the Beatific Vision. Before I say anything about the hymn, however, I had better say something about the bold Peter himself.

Himself.

To say that Peter was bold is something of an understatement. He was born in Brittany and endowed with an insatiable thirst for knowledge. He could turn his hand to any subject under the sun and, in time, was in great demand as a lecturer in philosophy in the schools of Paris no less. In this capacity he took on the great scholars of his day and reduced them to tears. As sometimes happens with such geniuses, he suddenly decided to adopt a bohemian way of life as a kind of free-lance troubadour, literally swinging from one extreme to another. Peter Abelard was cool long before being cool was cool.

I prefer to pass over in silence his early career as a popular songwriter. He would make many of our modern lyricists blush. It might be enough to mention that it is just as well that most of his vast collection of love songs has disappeared. Whether they were burnt by the Reformers or condemned by the Inquisition need not concern us here. This particular hymn, however, has survived for eight centuries, and with good reason. It is a sustained meditation on the final outcome of a good life in eternal rest.

Verse 1

Ah me! How calm and deep.

Let me pause for a moment at the first verse which really introduces us to the distinctive character of the entire poem. Out of piety I have kept the English version of this first verse in J.O’Conner’s translation (1870-1952), although it might be considered archaic today. He has managed the impossible by offering a fine translation of the first line, a line which is almost untranslatable – O quanta qualia, ‘Ah me! How calm and deep’ is perfect. For the remaining verses I have given my own almost literal translation of the original with no more than a clumsey attempt to keep to six syllables per line as does the original Latin.

Ah me! How calm and deep

those mighty Sabbath days,

the courts above do keep

with never-ending praise!

For weariness what rest,

for valour what reward,

when all in all the blest

indwelleth God the Lord!

+

O quanta, qualia

sunt illa sabbata,

quae semper celebrat

superna curia!

quae fessis requies,

quae merces fortibus,

cum erit omnia

Deus in omnibus!

The first thing that catches our attention is the fact that most of the furniture has been flitted out of heaven. There are no narrow gates to be negotiated, no trumpet blasts or harps in sight, no register. Nor is there even a passing reference to Purgatory or hell or last judgement.

The first two words, ‘Ah me!’ make it clear that our poet is emotionally as well as intellectually engaged with his theme. Everything in his life is consigned to the past and his eyes are fixed entirely on the future, described as ‘mighty Sabbath Days’. His starting point is a simple claim found in the Letter to the Hebrews that, when everything else has been swept away, ‘There remains a Sabbath rest for man’ (Hebrews 4.9-10).

That deceptively simple claim is an echo of the ambitious attempt of an ancient Jewish scribe to say something about the nature of God. The scribe is at home with the idea of a Creator God and feels free to develop this thought over a period of days which begin with chaos and end with ‘rest’. Each day brings into existence something that is ‘good’ and on the seventh day everything that comes from the hand of the creator is seen to be ‘very good’ (Genesis 1.1-2.4). If his epic had ended there, his would have been no different from the myths and legends so popular in ancient literature and published laboriously on tablets of clay or chiselled out on monuments of stone.

However, our wise Hebrew scribe had a trump card up his sleeve. The creator rested on the seventh day. We underestimate our scribe if we think he believed that the creator needed to stop at the weekend for a breather after the work of creating the universe. To see somebody in repose was to see him as he really is. As far as Peter Abelard was concerned, the Creator was no exception. The word used to describe this repose is ‘sabbath’ and is a brave attempt to capture something of the inner life of the Creator. What is revealed in creation is not the full story. The full story is in his Sabbath/rest. That is when God is really at himself.

Our scribe has something more to say. If man is created in the image and likeness of the creator, then he too must have more to him than meets the eye. He too must work for a time but find his ultimate destiny in Sabbath/rest. That one day in the week would be blessed and dedicated to celebrating his true identity. In time that sense of true identity, enshrined in the Sabbath rest, would be considered so sacred that to violate the Sabbath rest would amount to a desicration of the very nature of man, created in the image of God.

Our Christian churches have inherited this instinct for the sacredness of the Sabbath, some more than others. In our Catholic tradition those who consistently choose to ignore the Sabbath rest not only put their eternal destiny at risk, but diminish the quality of their life on earth. Peter Abelard composed his hymn to be sung in the local Convent each Sabbath day in the year. For a time, for obvious reasons, it was featured on the Solemnity of All Saints. Meantime, it seems to have gone into exile.

Verse 2

Jerusalem.

Almost every word in this verse contains an allusion to the Gospel. Pride of place is given to Jerusalem. All four Evangelists are aware of the importance of this city in the history of Israel. Saint Luke particularly dedicates much of his Gospel to Jesus’ final journey to the Holy City and does so with a solemn introduction:

‘The days were fulfilled

for him to be taken up into heaven

and he set his face resolutely to go to Jerusalem’ (Luke 9.51).

We are never allowed to lose sight of this destination. Matthew and Mark attach similar importance to that fateful journey and Saint John describes in detail the experience of five such pilgrimages.

As we move beyond the Gospel narratives, Jerusalem takes on an even more mystical meaning to become the image of paradise. The author of the Apocalypse claims to have been caught up in a vision of Jerusalem: ‘I saw the Holy City, the New Jerusalem, coming down out of heaven from God’ (Apocalypse 21.1ff). For our poet it is a place of ‘timeless peace’, of ‘supreme happiness’, of ‘highest hopes fulfilled’, of ‘an end to restless yearnings’ of the human heart. The verse expands the memorable words of Saint Augustine: ‘Our heart is restless till it rests in you, O Lord’ in an attempt to escape from stereotyped images of heaven.

Indeed, Jerusalem

is that praise-worthy town,

where reigns a timeless peace

in happiness supreme.

No hopes can e’r surpass,

the object of our dreams,

the prize exceeds by far

the yearning in our hearts.

+

Vere Jerusalem

est illa civitas

cuius pax iugis est,

summa iucunditas,

ubi non praevenit

rem desiderium,

nec desiderio

minus est praemium.

Verse 3

What king, what court, what palace?

As a descendant of King David, Jesus could indeed lay claim to royal blood but his kingdom was not of this world (John 18.36). Jesus’ seven parables of the kingdom, that Matthew 13 gathered together, make this only too clear. Verse 3 moves quickly beyond the image of an earthly kingdom with courtiers and palaces, so popular in Christian art, to a kingdom of peace, repose and joy and hints that it is beyond human capacity to describe such a place.

What king is this, what court,

what palace can this be?

Such peace and such repose

such joy beyond compare!

Those alone who enter there

can hope to speak of it,

if what they now behold

is not beyond their skill.

+

Quis rex! Quae curia!

Quale palatium!

Quae pax! Quae requies!

Quod illud gaudium!

Huius participes

exponant gloriae,

si quantum sentient,

possint exprimere.

Verse 4

Return from exile.

Life, meantime, is seen as a time of exile from our true home. The fall from grace had banished Adam and Eve from their home and their descendants, led by Cain, were destined to be ‘fugitives and wanderers’ on earth (Genesis 4.13). The father of the race, Abraham, had been instructed to leave behind everything that made for security and make for an undefined destination (Genesis 12.1ff). Later generations would describe their ancestor as ‘a wandering Aramean’ (Deuteronomy 26.5). Moses had journeyed for forty years towards a promised land. In the end he was allowed only to wonder at the view from a distance (Deuteronomy 34.1ff). The memory of their exile in Babylon gives way to the prospect of the longed-for return home of a worthy remnant. The influence of faithful prayer would determine the outcome of life’s pilgrimage.

It falls to us meantime

to raise our minds on high,

our home in heavenly bliss

to seek with constant prayer,

our path to Sion’s rest

from distant Babylon,

home at last from exile,

long-suffered for our sins.

+

Nostrum est interim

mentem erigere

Et totis patriam

votis appetere,

et ad Jerusalem

a Babylonia,

post longa regredi

tandem exilia.

Verse 5

We sing our songs

After a passing glance over a world of pain now left behind, our poet quickly returns to his new heavenly domain. In exile, the Jews had been asked by the residents to ‘sing us one of your songs’, only to be told that this was too much to ask of forlorn refugees far from their native home (Psalm 137.3). Now at last, no longer exiles, they gladly sing their songs of thanksgiving.

There, every evil gone,

and banished from our lives,

safe now, dear Sion’s songs,

we sing with voices raised,

for every gracious gift

your blessed ones return

to you our praise, O Lord.

+

Illic, molestiis

finitis omnibus,

securi cantica

Sion cantabimus,

et iuges gratias

et donis gratiae

Beata refert

plebs tibi, domine.

Verse 6

Unending Jubilee.

Our poet finds a foreshadowing of the wonders of eternal life in the religious observances of Israel. Creation itself was a kind of cosmic liturgical calendar. The Genesis Creation narrative had already demonstrated a national sense of the great liturgical seasons dictated by the phases of the moon as ‘signs and seasons.’ The weekly Sabbath observance is blessed as an integral part of this governance of daily life. The recurring Jubilee each twenty-five years would sanctify each generation. Sabbath rest follows Sabbath rest in an unending sequence, no longer marking the limitations of time imposed on human life, but celebrating its timeless endurance.

Our poet now, belatedly, makes room for others in that heavenly scene. Men and angels join in their chorus, as heaven and earth are at peace at last as they share their hymn of praise.

There, Sabbath follows on

and Sabbath follows on,

there is no end to joy

for those who keep this feast.

Nor ever can there end

such Jubilee for us

who share the hymn of praise

at one with angel choirs.

+

Illic ex sabbato

succedet sabbatum.

Perpes laetitia

Sabbatizantium.

Nec ineffabiles

cessabunt iubili,

quos decantabimus

et nos et angeli

Verse 7

The Final Doxology

As often happens with medieval Latin hymns, the final Doxology may not be the work of the original poet, but was added later to render the hymn suitable for liturgical use. Whether this doxology is the work of Abelard or somebody else is open to conjecture. However, it almost defies translation. The Father stands at the head of the Trinity of divine persons as the source of all life and this includes the life of the divine Son (by way of generation and not creation). The Spirit proceeds from both Father and Son. By the time our hymn was composed that much of the theology of the blessed Trinity was already well established in the creeds of the Church.

To the eternal Lord

let glory ever be,

of whom, through whom, in whom

all things come to exist;

The Father source of life,

to whom the Son is born,

the Spirit thus proceeds

from Father and from Son.

+

Perenni Domino

perpes sit Gloria,

ex quo sunt, per quem sunt,

in quo sunt omnia;

Ex quo, Pater est;

Per quem sunt, Filius;

In quo sunt Patris et

Filii Spiritus.

The last word must lie with Jesus himself. The Evangelist Matthew records his claim to a unique relationship with God the Father, a relationship in which they share the infinities of divine life. From within these infinities Jesus choses the one which best reveals his true identity. This is his gift to the world: He is the incarnation of the Sabbath rest:

All things have been delivered to me by my Father,

and no one knows the Son except the Father,

and no one knows the Father except the Son

and anyone to whom the Son chooses to reveal him.

Come to me, all who labour and are heavy laden,

and I will give you rest.

Take my yoke upon you,

and learn from me;

for I am gentle and lowly in heart,

and you will find rest for your souls.

For my yoke is easy, and my burden light. (Matthew 11.25-30).

We were given special permission by St Augustines in Coatbridge to publish the works of the late Canon Jim Foley. You can find the rest of his works here.

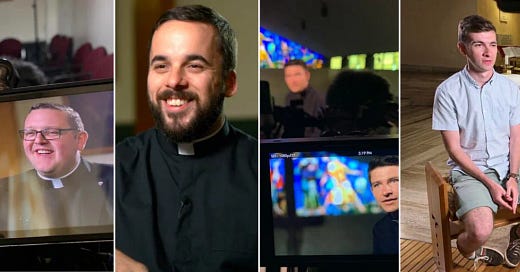

Discerning a Path to the Priesthood

By Fr Mark Impson, Vocations Director of RCD of Aberdeen

These days it takes a lot of courage to follow a vocation to the priesthood especially because, in our society, it is a lifestyle which is so counter-cultural. For men who do feel that God is calling them to this way of life there is a process which needs to be followed.

The Net Widens: Youth ministry in Scotland

By Sarah Rae LaValla, Team Supervisor of Net Ministries Scotland.

“Let Charity Move You to Reply”

-St. Columbanus

Over Christmas break, I finally sat down and watched the highly appraised series, The Chosen. For those of you who are not familiar with it, the historical drama aired in 2019 and is a television series depicting the life of Jesus Christ. The eight episodes of the first season are packed with content that I will not attempt to cover. Yet, I want to highlight one simple moment that struck me deeply.

If your appetite was wetted this week to learn more about St Thomas Aquinas then have a listen to this talk by Fr Paul Murray OP. St Thomas is well known for his scholasticism and works like the Summa, but is less appreciated as a Poet and Contemplative. Fr Murray (who wrote a book on the subject) speaks about the Angelic Doctors more contemplative works.

Saint Voloc, St. Glascian, St Mittan and St. Adamnan of Coldingham.

Over the next few days we have a few lesser known Scottish Saints from different parts of Scotland worth a mention. Here is just a brief summary.

St Voloc, Feast Day 29th January, 5th-6th Century

St Voloc was said to be Irish and moved to the Northern parts of Scotland to spread the faith. It was here he was raised to Episcopal rank and laboured into long old age, when at his death, angels were said to surround his bed. For his own sins and those who he laboured for he lived a life of great austerity. His house was made of woven reeds and had much regard for the poor. His life was one of holiness and many miracles were attributed to him. The chief area of his veneration was in Logic-Mar and Dunmeth Parishes which now lie in ruin, situated with Aboyne to the East and Ballater to its West. What was quite a shock when I was doing a bit of research on the fine Saint is that there is a St Voloc Festival in the American State of Texas! They dress up I think with Braveheart in mind but what an interesting link that is! There was of course in times past a fair held in Logic-Mar in his name, that included the pleasant ditty:

‘Wala-fair in Logic Mar, the Thirtieth day of Januar’.

St Glascian, Feast Day 30th January

Little is known of this Bishop who can also go by the spelling ‘Maglastian’. What we do know is that he was deemed an ‘illustrious Bishop’ in the time of King Achaius, a Scottish King who reigned in the same period as Charlemagne. He chief cultus was centred in what is now a small one street village called Kinglassie outside of Kirkcaldy in Fife. As you can imagine (if you have been keeping up with the Saints) there are a couple of wells in his name, including; St Glass’ Well in the same area and another in Dundrennan, Dumfries and Galloway.

St Adamnan of Coldingham, Feast Day 31st January, 686 AD approx.

This Saint has a wonderful story; a wild life the man lead before God intervened and wrought a dramatic conversion. So changed was Adamnan that he sought the counsel of an Irish Priest on what he should do and make penance for his sins. The Priest said he should only eat twice a week until they meet again. Unfortunately, the Irish Priest returned to Ireland and died shortily thereafter. But Adamnan was unperturbed and kept up this penance of only eating twice a week for the rest of his long life. He became a Monk and then Priest in the Abbey at Coldingham, which St Ebba was Abbot over, and gained the gift of Prophecy.

St Mittan, Feast Day 31st January

Much is unknown about this Saint but he was venerated, and a fair held in his name in the Southern Perthshire Parish of Kilmadock near Doune Castle.

If you have missed any past Coracles you can click here. Most of our past articles are on the roughbounds website as well as talks from Bishop Hugh Gilbert and the Highland Mens Conference.

Don’t forget we are Twits @stmoluagscoracle.

We have also started a GoFundMe page in the hope that if you are getting something out of the newsletters you may wish to contribute to their growth. If you want to go and have a look at our GoFundMe Page click the button below to find out more.

God Bless from Eric and Team