I believe in the resurrection of the body and in life everlasting.

‘But if there is no resurrection of the dead, then Christ has not been raised; if Christ has not been raised, then our preaching is in vain and your faith is in vain … If Christ has not been raised, your faith is futile and you are still in your sins. Then those also who have fallen asleep in Christ have perished. If for this life only we have hoped in Christ, we are of all people most to be pitied’ (1 Cor. 15:13-19).

The whole idea of the resurrection of the body has always been a difficult one for people to take on board, although they may be able to accept the concept of the soul being immortal. This was a real stumbling-block for people in St Paul’s time, but he proclaims joyfully, triumphantly even: “But in fact Christ has been raised from the dead, the first fruits of those who have fallen asleep” (1 Cor 15:20). There is a temptation to believe that when we die our bodies are no longer necessary; that our souls are what really count. In fact, we may even view our bodies as the negative, the bad, part of us. This has been a very common heresy right from the beginning of the Church. BUT human beings were uniquely created by God as body and soul; true, as a result of humanity’s fall from grace, our bodies age, grow weak, get in the way, as it were; but God intended from the beginning that we would one day live in glory with Him in spirit and flesh – glorified human flesh, just as Jesus now is. So, in one sense, we may still have the bodies we have now, with all the bits we don’t much like, but it won’t matter, not in their glorified state!

‘But someone will ask, ‘How are the dead raised? With what kind of body do they come?’ You foolish man! What you sow does not come to life unless it dies. And what you sow is not the body which is to be, but a bare kernel ... What is sown is perishable, what is raised is imperishable (1 Cor. 15:35-37, 42).

When we die our souls are temporarily separated from our physical bodies, but this is not a permanent state. At the end of time, when the world as we know it comes to an end and Jesus hands over everything to the Father, we will be reunited with our bodies, but bodies which are transformed. Then ‘on the Day of Judgement all human beings will appear in their own bodies before Christ’s tribunal to render an account of their own acts’ (CCC 1059). Jesus will be our Judge, the same Jesus who loved us enough to become man, to suffer humiliation, abuse, torture and a most cruel death for us; he will not be an unjust judge and we too will be judged according to our love. God once said to His chosen people as they were about to enter the Promised Land:

‘Look, today I call heaven and earth to witness. I am offering you life or death, blessing or curse. Choose life, then…’ (Deut 30:19).

He is saying the same to each of us; we must make our choice not just once, but every day of our lives, just as we are called every day of our lives to conversion, a turning back towards God. Even at the moment of our death we can make that choice for life or death, for life with God or life without God. The Catholic doctrine of the ‘Last Things’ offers us hope, a hope which those who do not believe in the final resurrection do not know. But God does not force anything, even Himself, on us; at the end of the day – at the end of my day – the choice is mine. A beautiful explanation of that future is:

‘Heaven is our total acceptance of God’s love; Hell is our total rejection of God’s love; and Purgatory is the gradual burning away of our resistance to God’s love. As such, they all begin here and now.’

‘At the evening of life, we shall be judged on our love’ (St John of the Cross).

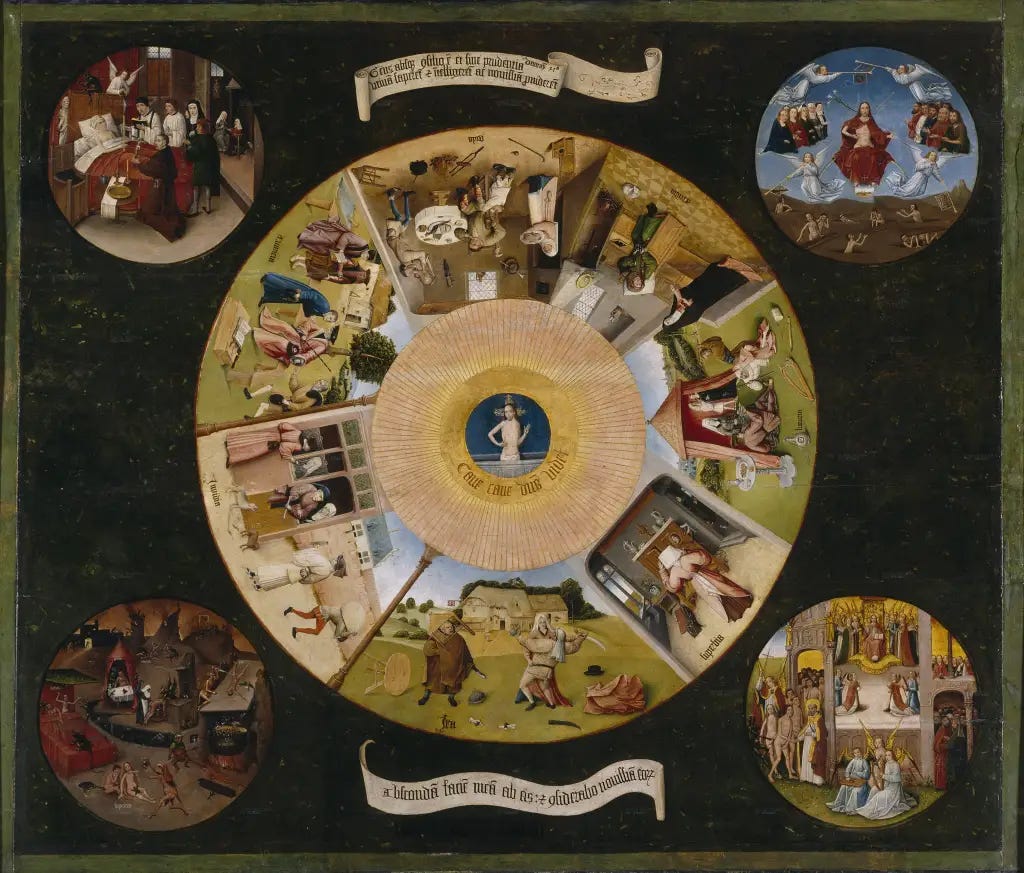

The Last Judgement

What we profess in the Creed, the resurrection of the dead, ‘of both the just and the unjust’ (Acts 24:15), will precede the Last Judgement. This will be ‘the hour when all who are in the tombs will hear [the Son of man’s] voice and come forth, those who have done good, to the resurrection of life, and those who have done evil, to the resurrection of judgement’ (Jn 5:28-29). Then Christ will come ‘in his glory … Before him will be gathered all the nations, and he will separate them one from another as a shepherd separates the sheep from the goats, and he will place the sheep at his right hand, but the goats at the left… And they will go away into eternal punishment, but the righteous into eternal life’ (Mt 25:31,32,46).

Hell

‘We cannot be united with God unless we freely choose to love Him. But we cannot love God if we sin gravely against Him, against our neighbours or against ourselves … This state of definitive self-exclusion from communion with God and the blessed is called hell.’ So says the Catechism (1033). We find many very graphic (and terrifying) images of hell in the Scriptures and elsewhere: again, we have only human images of our most frightening nightmares to go on. It’s a lot worse than the worst nightmare: hell is the eternal loss of God’s love. This is why the devil must be the unhappiest being (or rather, non-being) ever; he chose freely to reject God’s love and damned himself for all eternity. We do not know who, if anyone, will end up in hell; what we can do is pray that no one will.

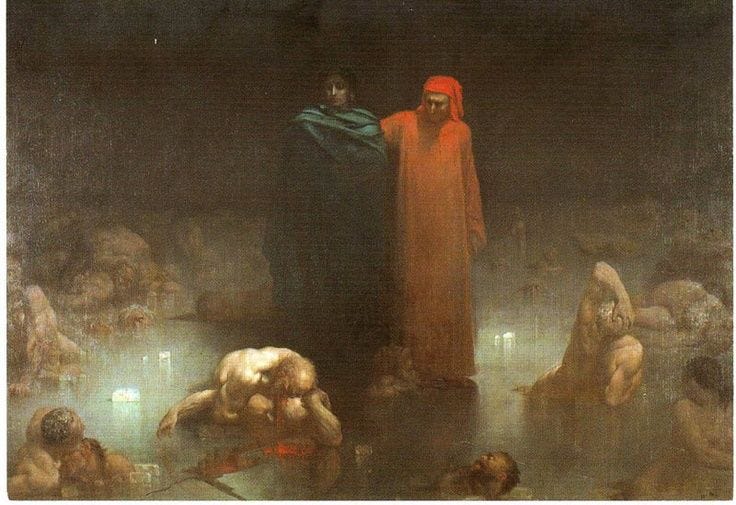

Purgatory

When we die, most of us are not yet ready or worthy to come face to face with God (unless we’re saints!). We need to clean up our act first, to be ‘purified’; this is what the word ‘purgatory’ means – ‘purification’, ‘cleansing’. Most of us will still be a bit on the grubby side when we die, although knowing this shouldn’t stop us trying to cleanse ourselves – with the help of prayer and the sacraments – while we’re still living in this world. We can pray also, and offer the sacrifice of the Mass, for those who have gone before us, that their purification will be achieved. Praying for our dead is a great act of kindness and love; we should continue to show solidarity with them even when we no longer see them, just as we think of or pray for those who are on a journey or in another country.

Heaven

Of course, we can’t really know what heaven will be like; we have only inadequate human comparisons to go by: eternal bliss, eternal rest, eternal getting-to-know-God etc. What we can believe is that heaven will mean seeing the Lord ‘as He is’, face-to-face, with no barriers between us.

And we all, with unveiled face, beholding the glory of the Lord, are being changed into his likeness from one degree of glory to another’ (2 Cor. 3:18).

Coming face to face with Love, being drawn in to share the inner life of God – this must be eternal blessedness, real happiness, not the weak and watery kind we may know in this life. This life is an exile; heaven is our true homeland.

Death

In order to get to heaven and to be united eternally with God, we first have to die. Death must come to us all and, though we may fear the manner of that death, we should not fear death itself, for death means leaving this place of exile and going to our heavenly homeland.

At a Catholic funeral the mourners hear these words:

‘Lord, for your faithful people life is changed, not ended.

When the body of our earthly dwelling lies in death

We gain an everlasting dwelling place in heaven’ (Preface of Christian Death 1).

At the end of our lives, the ‘perfect’ Christian death means that we die in God’s friendship, having confessed our sins, been reconciled and absolved, having received sacramental anointing, and the Eucharist one last time as ‘food for the journey’.

‘True and subsistent life consists in this: the Father, through the Son and in the Holy Spirit, pouring out his heavenly gifts on all things without exception. Thanks to his mercy, we too, men that we are, have received the inalienable promise of eternal life’ (St Cyril of Jerusalem).

Not a bad exchange!

By Eileen Clare Grant

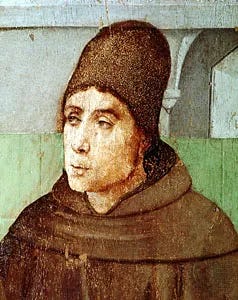

The 8th November is the Feast of Blessed John Duns Scotus, a peer and contemporary of St Thomas Aquinas, who among other things defended the Immaculate Conception of the Virgin Mary. Fr Robert Taylor of St Mary’s Cathedral in Edinburgh writes about him today.

Beautiful thank you 🙏