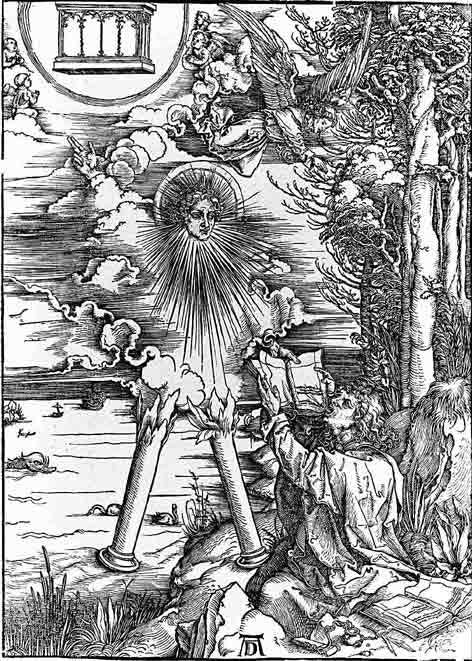

Albrecht Dürer: St. John Swallowing the little Book Presented by the Angel

Verse 5

Liber scriptus proferetur,

in quo totum continetur,

unde mundus judicetur.

+

The written book will be produced,

in which everything is recorded,

on which the world will be judged.

The Book of Life is the next well-attested ingredient in the inventory of these final days. Jesus had once assured his faithful disciples that ‘their names would one day be written in heaven’ (Luke 10.20). The Apocalypse gives a prominent place to the Book of Life when addressing the Last Judgement and the new heaven and the new earth (20.11ff). To date, this valuable source of classified information has escaped the attention of hackers.

Carvaggio: The Emmaus Road

Verse 6

Judex ergo cum sedebit,

quidquid latet apparebit:

nil inultum remanebit.

+

When the judge takes his place

whatever is hidden will then appear

nothing will remain unpunished.

Line 2 quotes Luke 8.17: ‘Nothing is hidden that will not be disclosed’. The message of the Sermon on the mount on the subject of retribution has found its way into the third line: ‘Truly I tell you, you will never get out until you have paid the last penny’ (Matthew 5.26). Absolutely nothing will escape the scrutiny of the judge as he issues a commensurate sentence.

Titian: Pieta

Verse 7

Quid sum miser tunc dicturus,

quem patronum rogaturus,

cum vix justus sit secures?

+

What then am I so miserable to plead

what advocate employ,

when even a just man is at risk?

The perspective now changes radically from the litany of ordeals just revealed, to the state of mind of one forlorn creature, the poet himself, who speaks as if he were already dead. Words fail him (What then am I to plead?). In life, others might have been called to enter a plea on his behalf but these have now melted away and he stands alone, isolated and vulnerable (What advocate employ?).

Against the measure of God’s infinite goodness, no creature can be considered worthy to enter his presence; not even those whose lives on earth were thought to be blameless. What hope is there for him (When even the just man is at risk). He ends with a quotation from the First Letter of Saint Peter ‘It is difficult for good people to be saved, what, then, will become of Godless sinners? (1 Peter 4.18).

Wikiart: William Holman Hunt: Light of the World

Verse 8

Rex tremendae majestatis,

qui salvandos salvas gratis,

salva me fons pietatis.

+

King of boundless majesty,

who saves the sinner gratis,

save me source of goodness.

The miserable creature of the previous verse is dwarfed by the majestic figure of the king. Everything the poet knows of him points to the gratuitous gifts of nature and grace bestowed on creation from the beginning (Genesis 1.32). We might suspect that there also lies behind this verse a thought so dear to Saint Paul. God loved us with a totally unselfish love, even when we were sinners and did so to the point of giving his only Son in the knowledge that he would be betrayed and put to death, though completely innocent (who saves the sinner gratis. cf Romans 5,8)). The final line of this verse reaches out to the prodigal Father for something even greater than ready pardon, reinstatement as his adopted son (save me source of goodness).

"晚禱 The Angelus" by 悠遊山城.樹玫瑰.庭園美食. is licensed under CC BY 2.0. By Millet.

Verse 9

Recordare, Jesu pie,

quod sum causa tuae viae:

Ne me perdas illa die.

+

Remember, dear Jesus,

that I am the reason for your journey here on earth:

Do not leave me to perish on that day.

Memory is one of the most important themes in both the Old and the New Testaments. It is inseparable from the thought of redemption. ‘But God remembered Noah’ (Genesis 8.1). In remembering Noah, the Creator set in motion the sequence of events that would restore his fortunes and save him, his family and mankind from total extinction. God’s remembering is the beginning of salvation.

The place of memory is established in a unique way at the Last Supper when Jesus told his disciples to ‘do this in memory of me’ (Luke 22.19). The blessing and consecration of the bread and wine as the body and blood of Christ were not intended simply as an expression of nostalgia for the past. They would render present the act of sacrifice that accomplished their redemption, the death and resurrection of Jesus.

Prophetic gestures, such as that performed by Jesus at the last supper, would set in motion the events they signified. They were effective signs of future redemption. This is equally true of the prophetic gestures of the Old Testament prophets as it is of the prophet Jesus in the New. ‘I see you are a prophet’ concluded the Samaritan woman, as Jesus offered her living waters welling up within her to eternal life, all in exchange for a cup of water! (John 4.19).

This prayer in verse 9 to be ‘remembered’, is a dynamic prayer to set in motion the redeeming grace of God for one man facing the most decisive moment in his existence, the decision about his final destiny. The ultimate expression of the place of memory in redemption is surely the parting request of the repentant thief: ‘Jesus, remember me when you come into your kingdom’ (Luke 23.42).

In our Sequence, the memory is focused on the fact that the salvation of the suppliant is the very reason for the Incarnation (Remember I am the reason for your journey). To bring the suppliant to a miserable end would signal the failure of Jesus’ purpose (Do not let me perish on that day).

The fact that this verse, like the others in this section of the poem, directs our attention to the fate of one sinner is in the spirit of the Good Shepherd who is prepared to abandon the ninety-nine sheep in order to rescue the one that was lost. The evangelist Saint John recalls Jesus’ intention: ‘I did not lose a single one of those you gave me’ (John 19.9).

Rawpixel: Christ Crucified by Velázquez

Verse 10

Quaerens me, sedisti lassus:

redemisti Crucem passus:

tantus labor non sit cassus.

+

You sought me out, when tired and weary:

You redeemed me by your suffering on the cross:

Let not such labour be in vain.

One of our poet’s most telling understatements is his subtle reference to the genuineness of Jesus’ humanity (‘when tired and weary’). One word (lassus/fatigued) is enough to carry our minds to the scene described at length by the evangelist Saint John (4.1ff). Exhausted, Jesus sat down to rest at Jacob’s well. The Gospel text could hardly describe more clearly the reality of the humanity of Jesus, Son of God. The divine person is incapable of experiencing fatigue. Not so his human nature which is like ours in all things but sin. In describing Jesus as tired and weary the Evangelist makes an uncompromising statement of the genuineness of his humanity, mysteriously joined to his divinity.

Our poet also wins our affection, as well as our sympathy, by identifying himself with the woman at Jacob’s well, an alien Samaritan, despised as much for her nationality as for her moral state (you sought me out). Further on, in verse 13, he develops this same sense of identity with another two marginalised members of society, Mary Magdalene and the repentant thief.

Please go onto the the next part here.

Written by Canon Foley

St Augustine’s Coatbridge has generously allowed us to reproduce some of the writing of the late Canon. If you want to read more of his writings please click here. St Augustine’s is also the home of Being Catholic TV, Scotland’s first Catholic TV channel.