Governmental rule has traditionally been identified in some sense as sacred. But Western democracies have generally abandoned such an identification. Is this a result of a growing realism about the uses and abuses of power, or is it a deep failing in a secularised approach to politics which is rendering Western societies increasingly ungovernable? Given Donald Trump’s recent presidential victory, what should we make of Trump’s Catholic, former éminence grise, Steve Bannon, whose his views have described thus:

His ideal society is not one where certain human types lord over others, but where considerations for spirituality and cultural essence guide social and political life. [1]

Such thoughts have been prompted by my having just completed approximately 330 hours of watching the Turkish TV epic, Diriliş: Ertuğrul [2]. The series is set in 13th century Anatolia and covers the various struggles which would ultimately result in the foundation of the Ottoman Empire by Ertuğrul’s son, Osman. It’s probably worth saying immediately that, on a straightforward level, it’s just an enjoyable adventure story which has some of the virtues of older Hollywood films and TV programmes: lots of intrigue, goodies and baddies, sword fighting, love interest and riding up and down spectacular countryside on horseback. It’s also been incredibly popular in much of the Islamic world and thus has the added attraction of giving some sort of insight into another way of looking at the world from the modernised norms of secular, Western culture. Once you get your head around the fact that our traditional heroes like the Crusaders and Byzantine Empire are their traditional enemies, you can settle down to an almost endless stream of enjoyable warrior bonding and damsels in distress.

But it’s that another way of looking at the world that I want to focus on here. The main element throughout is the sense of Ertuğrul’s sacred mission to impose justice on a chaotic world, and the daily presence of religion as a source of strength in those struggles. This theme was probably reinforced for me by reading Julius Evola at the time of much of my viewing. Whether or not the series is directly influenced by Evola’s Traditionalism, or indirectly by a common source in Islam, there are some striking echoes between Diriliş: Ertuğrul and Evola’s work that are worth pondering. [3] Evola emphasises the role of the priest/king in imposing the sacred on society, and, more generally, imposing form on the people’s chaotic psychological material:

Beneficial spiritual influences used to radiate upon the world of mortal beings from the mere presence of such men, from their ‘pontifical’ mediation, from the power of the rites that were rendered efficacious by their power, and from the institutions of which they were the centre. These influences permeated people’s thoughts, intentions and actions, ordering every aspect of their lives and constituting a fit foundation for luminous, spiritual realizations. [4]

Ertuğrul spends much of the series fighting against internal enemies who undermine the struggle to maintain Islamic rule usually for the sake of personal advantage or from a failure to uphold the traditional laws and customs of the tribe due to a lack of self-restraint and uncontrolled anger. He imposes external order by following the traditions of the tribe combined with clear-sighted decision making, and encourages development of character by example and individual punishment. There is mercy in Ertuğrul, but is usually reserved only to those who have made a radical change in their lives and personalities, particularly by becoming Muslim: a regular refrain throughout the series is that, ‘Mercy to the cruel is cruelty to the weak.’ In general, the need to use power in imposing order on the chaos of hostile enemies and individual psychology is emphasised, and Ertuğrul’s prophetic judgment often set against the more pragmatic and fallible judgments even of the well intentioned.

It is very easy to see analogies to these views in older Western thought. Plato in books 8 and 9 of the Republic draws constant connections between the order of society and the order of the soul. Aquinas argues as follows:

[I]n the individual man, the soul rules the body; and among the parts of the soul, the irascible and the concupiscible parts are ruled by reason. Likewise, among the members of a body, one, such as the heart or the head, is the principal and moves all the others. Therefore in every multitude there must be some governing power.

[…]

The greatness of kingly virtue also appears in this, that he bears a special likeness to God, since he does in his kingdom what God does in the world; wherefore in Exodus (22:9) the judges of the people are called gods, and also among the Romans the emperors received the appellative Divus. [5]

Now it is very easy to imagine some common responses to all this. The sacred is a fiction. Talk of the near divinity of kings is a disguise for the imposition of power in support of material interests. Evola is a Fascist or even worse. Ertuğrul as a TV series, whatever its merits as entertainment, also brings with it a taint of Turkish Nationalism weaponised in the interests of President Erdoğan’s authoritarianism. Taken together, this is a poisonous soup of fascism from which no political lessons should be drawn except for what to avoid. In many ways, I don’t disagree with such analyses: Traditionalism in the sense I am using it here, and particularly that version of it espoused by Evola, I take to be more of an interesting but often hostile conversation partner for Catholicism rather than something that should be a direct inspiration. However, Evola has some plausibility in claiming that, ‘My principles are only those that, before the French Revolution, every well-born person considered sane and normal.’ And given that for most of those 1789 years preceding that revolution -and indeed, in many ways until long after- those principles were those of Catholic Christianity (and magisterial Protestantism), it is rather an odd position, for Catholics at least, to privilege what has emerged only in late modernity rather than the accumulated wisdom of the centuries. Until very recently in Scotland, respect for religion and the monarchy was widespread. The virtues of the military life were valued and had formed the characters of most men. In particular, a warrior’s need for emotional restraint and obedience to one’s leaders was inculcated in the young and supported by popular entertainment. These are the main principles of Evola, they were the main principles which used to be widespread in Scotland, and they are still the principles to be found in this immensely popular TV series which presumably says something about the current culture of Turkey and much of the Islamic world. So why are we now so certain that there is nothing of value in them, and that what we have replaced them with is so obviously better?

I write this without much of a sense of how such questions should be answered. But what we, as Catholics and Scots, lack is much widespread thought on the fundamentals of political structure, rather than a mere tinkering with existing arrangements. Instead, I would focus on two questions which arise from the above reflections: how should Scottish politics encourage a link to the sacred, and how should it encourage a character among Scots that, instead of encouraging lack of emotional restraint, instead encourages self-control under the influence of that rational self which lies closest to the divine? Catholics will have their own specific answers to this, but putting the questions in this form might well encourage the contribution of allied spiritualities to our efforts and, at the least, a growing questioning of some of the assumptions of secular modernity.

By Stephen Watt

References and further reading:

[1] Benjamin R. Teitelbaum (2020) War for Eternity: the Return of Traditionalism and the Rise of the Populist Right, Penguin, Ebook, p.79

[2] At the time of writing, the best way to view this series is via YouTube: https://youtube.com/playlist?list=PLDoK5CcjJZA5l21jGd6PNUIpMtCUnKNeo&si=S2kNWXc51X4xwUQN English subtitles are available. The Wikipedia article on the series can be found https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dirili%C5%9F:_Ertu%C4%9Frul

[3] On Evola, see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Julius_Evola and on Traditionalism in general, my previous article in the Coracle https://stmoluagscoracle.substack.com/p/king-charles-iii-traditionalism-and

[4] Julius Evola (2018) Revolt against the Modern World. Inner Traditions. Ebook, p.62.

[5] De regno, chapter 1: https://isidore.co/aquinas/english/DeRegno.htm#1

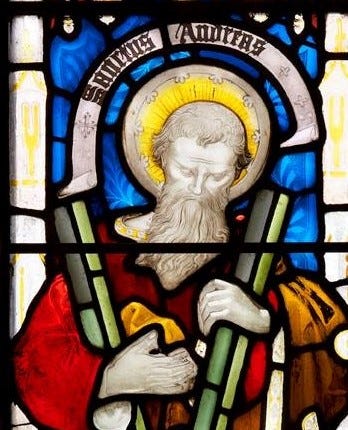

With the Feast of our nations Patron coming up why not try a traditional novena and read a little bit more about St Andrew.

I think the search for a sacred politics is a profound one. Unfortunately, authors like Evola are proposing a fascist (or super-fascist) solution to the problem of disenchantment. We need political forms of the sacred that can flourish and support multi-ethnic, religiously pluralistic democratic societies. It will require much work and imagination from Catholics! I attempted to articulate this problem in another online journal a few years back.

https://regensburgforum.com/2021/08/30/of-rights-and-rites/