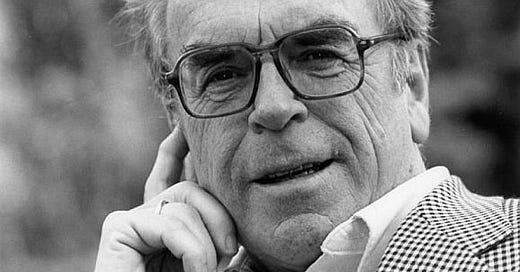

Moltmann

A review of the late Jurgen Moltmann, one of the most influential theologians of the 20th Century, and whose ideas could help us interpret Synodality and Pope Francis' open dialogue.

The German Protestant theologian, Jürgen Moltmann, died on 3 June 2024 at the age of 98. Sometimes described as the most influential theologian of the last half of the twentieth century, he was prolific in his writings and the subject of many obituaries and tributes on his death.

In the recommended reading below, I’ve included suggestions for a number of such tributes, and there is little point in repeating their details here. Instead, I’ll focus on a more personal response to his work. I first came across Moltmann on the recommendation of a deacon in the Scottish Episcopal Church whom I greatly liked. That deacon came from an evangelical background but with a strong focus on social action, and that’s not a bad prism through which to start an approach to Moltmann. Moltmann like many twentieth century Germans lived out his life in the shadow of the Second World War and particularly of the Holocaust, and it was his attempt to reconcile that suffering with the hope of salvation that can be seen as informing much of his work.

Moltmann was held as a prisoner of war in a number of places including Kilmarnock, where he was employed in constructing and repairing roads. During these periods, he began to read the New Testament and described his treatment by his former enemies as both ‘incredibly kind and yet deeply shaming’. (This combination of suffering and yet also an offering of a new hope through that experience is characteristic.) Following Karl Barth, he rejected a Christianity that was closely identified with existing society, but unlike Barth he emphasised the possibility of nevertheless finding hope in history and experience.

When I was first presented with Moltmann primarily through his book, The Crucified God, I was excited by a theologian that promised both radical rejection of actual social norms but also the prospect of an experience of God that was not simply founded on blind faith but on observable features of the world, in particular the hopefulness of resurrection and eschatology. But I’m afraid I also found the book rather dull and I struggled to finish it at the time. In retrospect, I don’t think this was entirely fair to Moltmann, but it felt like the stereotypical atmosphere of justice and peace Christianity at its worst: a rather complacent emphasis on the power of everyday lives and action, and a compete dismissal of anything that might burst into that world with angels and fire and trumpets. I wanted an apocalypse of divine glory; and what I thought I got was Greenham Common and consciousness raising.

This sort of criticism of Moltmann is still common among more conservative theologians and is reflected in Carl Trueman’s assessment of his career:

For Moltmann, the categories of this immediate world context drove his theology. He had no sense of transcendence and no final sense that God’s Word breaks into this world from outside, rather than merely emerging as part of an immanent historical process. And those who marry their theology to immanence are oddly doomed to divorce their theology from relevance. That is why his contributions to Liberation Theology, Christology, social Trinitarianism, theodicy, eschatology, and political theology are all now museum pieces, fodder for courses in modern church history rather than systematics.

So why don’t I think this is entirely fair to Moltmann? The underlying charge from Trueman that Moltmann is too immersed in the values of the existing world to provide a truly Christian challenge: whether the therapeutic benevolence of Western Christian communities or the Marxism of Latin American guerillas, both are those of this world rather than the next. To respond to this underlying charge, I’d distinguish between (as Richard Bauckham puts it) Moltmann’s ‘openness to dialogue’ as a principle, and how he chooses to apply that principle. Moltmann is open in principle to recognising the signs of hope in the present, and will thus engage in dialogue with current values and movements in order to explore that hope. But as Bauckham also notes,

[Moltmann] resists the idea of creating a theological ‘system,’ as a finished achievement of one theologian, and stresses the provisionality of all theological work and the ability of one theologian only to contribute to the continuing discussion within an ecumenical community of theologians…

It is therefore possible to think that Moltmann’s principle of open dialogue to explore the signs of a truly Christian hope is a worthwhile one, while accepting that many of the ways he applies that principle are very much provisional and even (as Trueman puts it) ‘museum pieces’. An example of this might be his final two chapters in The Crucified God where the dialogue partners are Freudian psychology and Marxism. That strikes me as more of an obvious choice in 1973 than it would be now, but even then, Moltmann is explicit that his exploration of such specific dialogues is only representative of possibilities:

Of course, this dialogue is only an extract from the many-layered pattern of Christian anthropology today, open to the world as it must necessarily be. It can therefore lay no claim to completeness. But it did seem more important to present the consequences of the theology of the cross at one point than to keep to abstract generalizations.

In broad terms, I think it is entirely plausible to find in Moltmann a helpful emphasis on the importance of dialogue with this world and its values, so long as what is primarily sought are the traces of the gold dust of eschatological hope rather than a resignation to the dross of materialist values. (In 2024, for example, why not a dialogue with the Mark Fisher’s criticism of ‘capitalist realism’ or with Julius Evola’s idea of society as embodying a sacred hierarchy?) For individual Catholics, this may be less about engaging with ideas and more about meeting people which became an increasingly important part of Moltmann’s approach in his later theology. Although I don’t have the space to do this topic justice here, and despite the fact that I am not aware of any acknowledged direct influence from Moltmann, it is clear that much of Pope Francis’s emphasis on synodality and personal encounter might be illuminated by a more detailed comparison of his views and Moltmann’s. Certainly, the influence of Moltmann on Latin American Jesuits in general is well documented, not least by the discovery of a copy of The Crucified God next to the body of the martyred Father Juan Ramon Moreno.

Finally, however, I think it important to provide two warnings about Moltmann’s approach. First, Moltmann’s approach is extremely Protestant. For example, in The Crucified God, he talks of Christian theology primarily thinking ‘traditionally in terms of a dialectic of law and freedom’. While that's always going to be an important topic, I'm not sure it's so central to the rather richer universe of Catholic theology as it is to German Protestantism. And acknowledging this is to suggest that too strong a focus on liberation in Moltmann’s theology rather than, say, divinisation may itself be a misdirection. Linked to this is a second warning: as Nietzsche puts it, ‘Whoever fights monsters should see to it that in the process he does not become a monster. And when you look long into an abyss, the abyss also looks into you.’ Staring into the world can easily have you lost in the world unless you approach it with a strong formation in Catholicism: although there is a need to engage in an open dialogue with other non-Christian and non-Catholic approaches and people, there is a primary need to engage in the living body of Christ which is the Catholic Church, both intellectually and sacramentally: ‘You are the salt of the earth. But if the salt lose its savour, wherewith shall it be salted?’ Whether Moltmann always does this, even in his own Protestant terms, is perhaps open to doubt.

Stephen Watt

Recommended reading and references:

BBC Radio 4, ‘A suffering God’, Beyond belief, available at https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m0021qjc

Obituary by Zoran Grozdanov, BYU Law, available at https://talkabout.iclrs.org/2024/07/08/revolutionary-in-theology-in-memoriam-jurgen-moltmann/

Carl Trueman, ‘The night I met Jürgen Moltmann’, available at https://eppc.org/publication/the-night-i-met-jurgen-moltmann/

Church Times, 27 March 2020, ‘Listening for God’s eternal “Yes” ‘, archived edition available at https://archive.ph/MaOig

Bauckham, Richard (1997) ‘Jürgen Moltmann’ in David F. Ford (ed.) The Modern Theologians, Oxford, Blackwell Publishers, pp.209-224.

Moltmann, Jürgen (1974), The Crucified God, London, SCM Press

We are in the middle of the ‘dog days of summer’ (yes that’s a thing!) with July gone and an uncertain August nearing its end. There are many local Scottish Saints for us to read into and devote sometime in prayer with. Go over to our ministry site: www.maryswell.net/augustsaints to learn more about some of them. They include St Walthen of Melrose, St Berchan of Renfrewshire and Argyll, St Blaan of Bute and the great St Aidan of Lindisfarne.