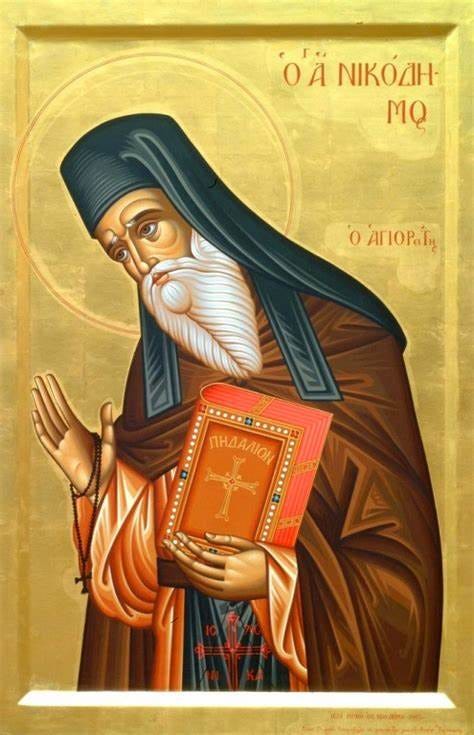

St Nikodimos of the Holy Mountain

Over Advent, I began to read The Philokalia, the collection of spiritual writings which is central to Orthodox Christianity. In the English translation, the definition of the term ‘theology’ was given in the glossary as follows:

Theology denotes in these texts far more than learning about God and religious doctrine acquired through academic study. It signifies active and conscious participation in or perception of the realities of the divine world - in other words, the realisation of spiritual knowledge. To be a theologian in the full sense, therefore, presupposes the attainment of the state of stillness and dispassion, itself the concomitant of pure and undistracted prayer….

As well as being stimulated to think about the nature of theology by this definition, I was also teaching a course on ancient philosophy which focused on Pierre Hadot’s view of such philosophy as being primarily concerned with personal transformation rather than the modern practice of academic philosophy as research. Both of these occasions have encouraged me to think about the nature of study particularly in the area of the laity studying theology or, more generally, of what T. S. Eliot called the ‘permanent things’, but which might also be termed the ‘deepest things’.

Within my own academic discipline of philosophy, there has been considerable debate about whether the subject has taken a wrong turning. The precise nature of such a wrong turning is itself disputed, but a recognisable thread within such debates is whether philosophy as practised within the university has become in some way a desiccated discipline divorced from any substance of true concern to human beings and instead reduced to a merely technical discipline carried out mainly in journals which, rarely actually read, only serve the purpose of credentials for access to and promotion within universities. St Moluag’s Coracle itself was founded in part with the desire to promote a deeper engagement with intellectually rich Catholicism among interested readers in Scotland. But how precisely is this deeper engagement supposed to work?

Imagine a world in which Artificial Intelligence had been developed to such an extent that it was able to produce academic journal articles of the highest quality. Such articles produced by machine and untroubled by any human reader would then be responded to by other artificial intelligence programmes. And so on. The results of these articles would be of the highest possible academic standard. The responses to them would also be of the highest possible academic standard. No human beings would actually read them of course. But since this is close to the current situation anyway and the quality of the articles and research findings would be massively increased, why should we not welcome such a future? What would be lacking?

This is of course an absurd version of the future and a gently satirical version of the present. However, it is sufficiently similar to existing conditions for it perhaps to serve as a troubling suggestion for academic philosophy and theology. Debates within the Academy are conducted with little attention from those outside the Academy and to the extent that the results are exported to non-professionals, these results are simply presented as expert wisdom to be received as best they can be without challenge or question. When in addition the modern academic ethos of an incessant push for publication and personal recognition is added in, the resulting creation of churning novelty delivered to a largely uncomprehending and passive laity on the basis of a credentialled authority is recognisable as a distortion but only a slight one of the current position.

I have no wish in this article to challenge the internal workings of either philosophy or theology university departments: let’s assume that they should go on as they are, and wish them well. However, I do want to think about how such subjects which involve the quest for the deepest aspects of life should be pursued within those groups which are not professionals within the university but which nevertheless possess the general intelligence, desire and even need to learn more about these depths. From such a perspective, what is lacking in the AI future scenario and in the distorted caricature of existing academic life is the transformative influence upon human character. Science as a research discipline can still deliver results, crudely, if bridges don’t fall down and if computers work faster. The humanities can only deliver results if people, real and many people, are transformed by them. Whether the results of the inquiries into the deepest things are simply not widely published or whether the results remain opaque due to technical complexity, people are unable to internalise the results of these investigations.

But here's an alternative dystopian vision. Instead of academically rigorous but ignored theology and philosophy, we have a lively intellectual culture amongst the laity but informed more by their prejudices and ignorance than by academic standards and concern for the truth. Although such a scenario may incorporate the elements of personal search that are lacking in the earlier scenarios, it now lacks a realistic orientation towards the truth and tends to result in an undermining of an essential docility to authority and humble awareness of our own epistemic inadequacies.

The task is to steer between the Scylla of undisciplined personal search and the Charybdis of incomprehensible and imposed authority. But how is this middle course to be found? Many of the articles I have written for the Coracle have been explorations of philosophers and thinkers who are not Catholic. Among these, I have written about René Guénon and Martin Heidegger both of whom were to an extent actively hostile to Catholicism. And yet I have argued that both may be and perhaps should be read by Catholics with the time and inclination. Why? Life is short and the 2000 years of Catholic thought surely contain enough to take up most people’s life spans if they do not have the luxury of devoting themselves to full time study. Indeed, devoting time to thinkers who are at best tangential to Catholic doctrine is arguably not only a waste of time but runs the risk of stirring up dangerous ideas and inclinations opposed to Catholicism but which the relatively unprepared may be unable to reject. Why then have I urged our readers at least to consider engagement with such writers?

Like it or not even the most devout Catholic in the modern, secularised West lives in a society which is not entirely formed by a thorough-going Catholic culture. Although more of us have gone to university and are literate at a higher level than any previous population, much of that education has been in a form that is either antithetical to or distanced from Catholic norms. (Our heads are full of Elvis Presley, Jean-Paul Sartre and pornography.) So if we ought to take seriously the sort of personal search which starts from our desires and thoughts then those desires and thoughts are likely to be coloured at least in part by the trappings of our secularised age. Unlike academic theology and philosophy, personal transformation is at least one key element if not the key element of theology in the sense suggested by the definition of The Philokalia. And authors such as Guénon or Heidegger or whoever else we may come up with may well be better initial guides to our current spiritual state than the Doctors of the church of a different time and place. So one reason for engaging with non-Catholic thinkers is that they might speak to us in our fallen modernity rather more clearly than do those more central to our tradition. On the other hand, the route out of such perplexities must involve the cultivation of getting closer to God in large part through being able to see the world through the perspective of those who are already closer to him: seeing where we are may involve non-Catholic thinkers, but seeing our way out will primarily involve the Saints.

So here is the difficult mix that any lay intellectual engagement with the deepest, most permanent things should produce. It must be personal in a way that is just not a passive acceptance of truths articulated and imposed from on high. It must truly involve a personal commitment and involvement with their exploration, but such a personal commitment must avoid the risk of deviation from the truth due to ignorance and poor spiritual preparation. It must therefore involve a docility towards those far more advanced on the path towards God which allows the correction of tendencies towards error. Finally, this difficult mix must take place in a time and space of sacred waiting: as The Philokalia definition states, theology in this sense presupposes the attainment of the state of stillness and dispassion which is the concomitant of prayer.

Stephen Watt