Hidden Scottish Catholicism: Finding the Artefacts

Kirsten Schouwenaars-Harms reveals some of the artefacts of our Catholic past in Scotland.

The dawn of Christianity brought the birth of an earthly pilgrimage for all believers, one that has unification with Christ as its end goal. To aid this pilgrimage, as well as spiritual growth and remind them of the ultimate sacrifice that Christ made for them, most Christians will have, at some point, used certain artefacts. Items such as crucifixes, rosaries, prayer cards and many others have been around for as long as believers have been. And therefore with the arrival of Christianity in Scotland, religious artefacts equally appeared. Many of these religious items have been lost over the years. Buried with those who have died, lost in the ruins of homes and ecclesiastical buildings, or taken back to nature with time. There is also evidence that during the Reformation Catholic artefacts were not only removed from churches but were hidden away, awaiting a restoration of Catholicism. Excavations, certainly over the recent century, have uncovered many beautiful and interesting items with their own story to tell. Let us rediscover some of them.

The National Museum

During the 2014 excavations in Balmaghie, Kirkcudbrightshire, a large section of silver, gold and other materials was found by a metal detectorist, known as the Galloway Hoard. Among these extraordinary riches stands out an ornamented silver pectoral cross. It is decorated with gold and niello inlay and features symbols of the four evangelists. The cross still has the pendant fitting in place with a silver wire chain threaded through it. Indicating that the cross was likely used by a high-ranking cleric, such as a bishop, abbot or abbess just before being buried. The carving of the cross is particularly beautiful and well-maintained for such an old object. The whole of the hidden treasure of the Galloway Hoard is now available to admire in the National Museum of Scotland.

While the Balmaghie excavations produced some truly beautiful items, the area was never used for ecclesiastical purposes. When digging does occur in sites that used to house churches or monastic buildings it is not uncommon that beautiful and interesting artefacts are unearthed. A good example of this is a 13th century seal from Inchaffray Abbey. The abbey was situated near the village of Madderty, midway between Perth and Crieff in Strathearn. The only traces of the abbey that are still visible are an earth mound and some walls on rising ground which once formed an island where the abbey stood. This religious house was dedicated to the Virgin Mary, and John the Evangelist, and granted to the Augustinian Friars of Scone Abbey. Here a double-sided circular bronze seal-matrix was re-discovered. It has three pierced lugs and corresponding pegs created this way to make a double-sided wax impression. On the obverse, we can find the Abbey itself with a central canopy under which a nimbed St John stands with a quill pen and book. There is a legend within pearled borders. On the reverse is a cusped border of eight points and the eagle of St John the Evangelist holding a scroll with a legend while on the surround the same legend as on the obverse can be seen. Seals were important artefacts in religious houses. They were used as a sign of legitimacy and were often only allowed to be handled by those in the highest office. The Inchaffreay seal is a particularly nice example and can be admired in the British Museum.

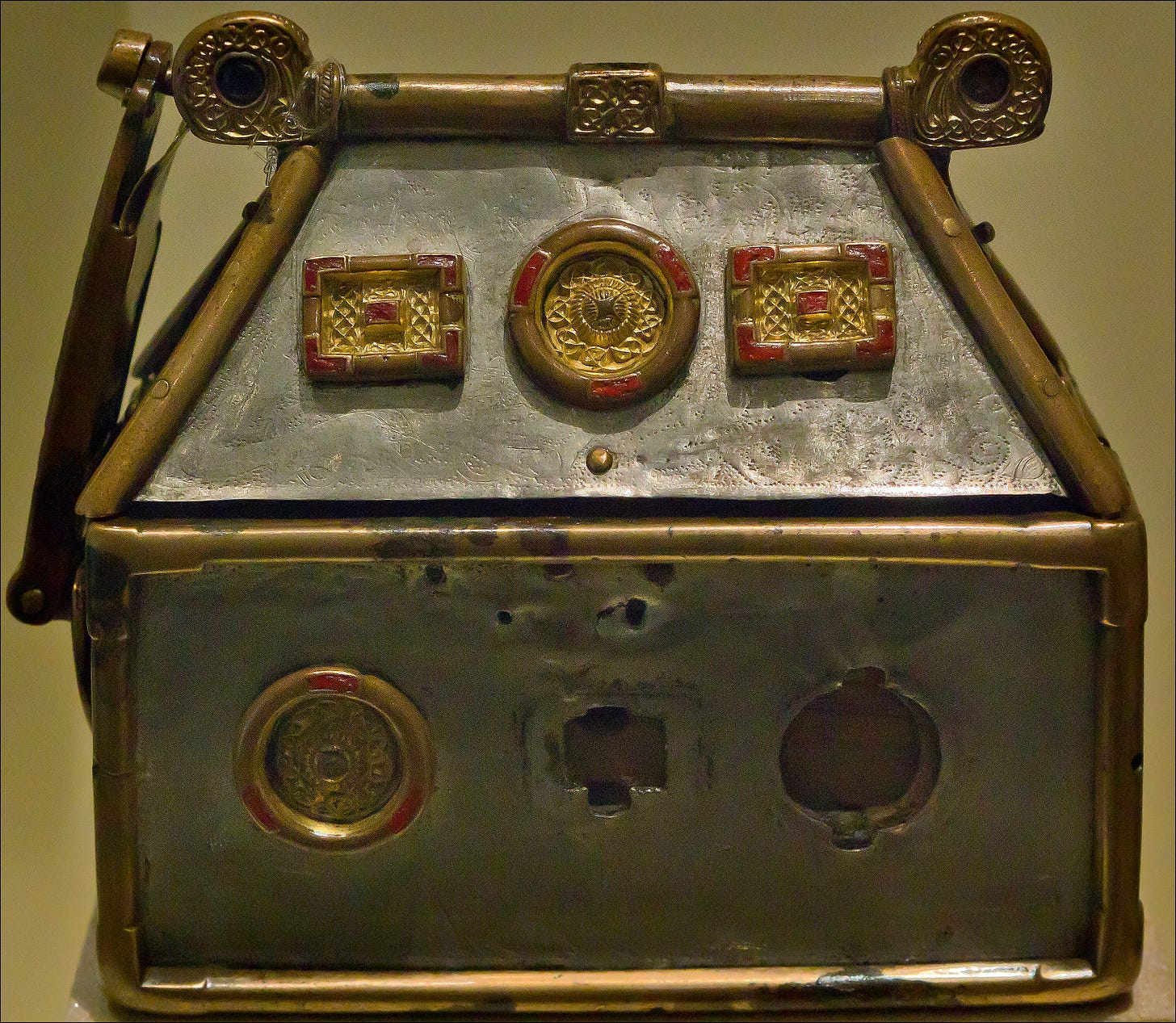

"The Monymusk Reliquary" by dun_deagh is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

Another outstanding item to note is the Monymusk Reliquary. Although never truly lost it was kept in private possession for many years but now to be admired in the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh. This 8th century house-shape casket is made of wood and metal. It is one of the finest of the six Celtic reliquaries known to exist, most likely made by the monks of Iona Abbey. This is probably attributed to the idea that it was thought that the reliquary was used to have contained relics of St. Columba, a suggestion that is, these days, disputed by many scholars. The importance of the object shows in that it was carried for centuries by its custodian before the Scottish army in battle. Most famously during the Battle of Bannockburn (1314) in which the Scottish army who were victorious against the army of King Edward II of England.

Other Catholic artefacts can be found in private collections in Scotland. In Castle Fraser, near Inverurie, there is a small room, where we can view one of the oldest artefacts of the castle, a beautiful 14th century Agnus Dei, the Lamb of God, carved out of a circular wooden slap. The object was regarded as a holy object or a talisman, and the image of a sheep and flag was one that appears on many Knights Templar seals. Because of its pre-reformation production very few such artefacts remain. Many noble families in the Northeasterly region of Scotland remained faithful to the traditional faith of Catholicism, which their location of the secluded rugged highlands allowed them to do. Castle Fraser hides a few symbols that show that they most likely stayed faithful in this difficult time. Good examples of this are the Arma Christi, a Catholic symbol, on the outside wall, depicting the 5 wounds of Christ, as well as a likely priest hole in front of the heart. But in my opinion, the Angus Dei, in its magnificent simplicity, is the most beautiful piece of Catholic history to be admired in the castle.

This simplicity translates to what Jesus taught us: “And he said to them, “Take care! Be on your guard against all kinds of greed; for one’s life does not consist in the abundance of possessions.” (Lk 12:15). After all most of the artifacts that have been used over the years will be those of laity, and often these will have been modest, but no less important to those who used them in their spiritual journey. Between 1975 and 1978 large excavations were done in Perth Highstreet. Perth was a medieval centre for local pilgrimage, St John’s Kirk held a relic of St Eloi and as such we can expect that any digging in this ancient city will yield interesting artefacts. The digging unearthed a range of pilgrimage souvenirs including a badge of St Andrew, two ampullae of St Thomas Becket from Canterbury, and two scallop shells of St James from Santiago de Compostella, Spain. This certainly indicates a high concentration of pilgrims to the city. Badges and ampullae were worn while travelling and allowed others to identify the wearer as a pilgrim and the saint they were visiting. They showed the wearer's special relationship with a particular saint and could be used to touch for instance a saint’s tomb to make the badge into a third-class relic, thus finding religious items as these is very special indeed. Like many religious artefacts, the medieval St Andrews badge can be found in a museum, in this case, the Perth Museum and Art Gallery, where further investigation into its history can take place.

See https://electricscotland.com/history/st_andrew.htm

The fact that museums want to display them for future generations to admire shows their importance. These objects have been used, and still are, to aid in worship, festivals, rites of passage, or as daily reminders to believers in Christ, their traditions are our traditions, and their identity is our identity, even if the passing of time has caused changes to occur. The artefacts can be a means of signifying specialness, a visible link to the community and its history; a symbol of key principles and beliefs, or a sign of commitment and belonging. Even if we live in a more and more secular society, the importance of the items cannot be denied and should never be forgotten. Rediscovering them, highlighting their importance and trying to find their, often hidden stories, are efforts that must be maintained as part of all our religious and cultural heritage. There is still much value in these artefacts, they and their stories can serve in an evangelizing manner, allowing the Holy Spirit to work in our imagination. Finding these hidden artefacts can be an opportunity to support the faith and affirm their religious practices for the future.

Coming up this month we have the feast of St Buite; of Irish origin and compared to St Bede. We also have the mercurial but fantastic St Obert, who in the early days of the reformation in Perth got a lot of young bakers in trouble. We also get an interesting window into 9th century north-eastern Scotland with the feast of the multi-lingual St Manire. The 23rd of this month sees the feast of St Mayota, one of a small number of women canonized in Scotland. The story of St Mayota parallels that of the other women listed in the Aberdeen breviary which unfortunately often tells us very little. However it appears the most consistent place of association was Abernethy.

Finally, as many of us tuck into our turkeys, we could raise a glass to St Bathan. This Berwickshire Saint was mentioned in a letter dated to 642AD by Pope John IV who seems to have specially associated him with Scotland.