Celebrity Conversions

Do celebrity conversions tell us anything about the state of Catholicism in the West? Stephen Watt writes about it here.

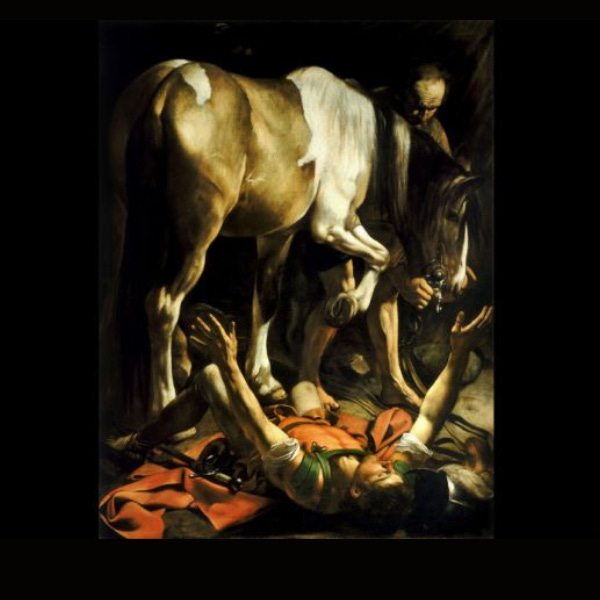

The conversion of Saint Paul, by Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio.

Are there signs of a revival in Christianity and even in Catholicism in the West? A number of recent celebrity conversions as well as endorsements of the benefits of cultural Christianity might seem to suggest this. But do we really have reason to find hope in this phenomenon?

The latest outburst of hope in the post-Christian West seems to centre on a number of celebrity conversions to Christianity, and also on a few celebrity near misses: well-kent figures who, while unable to describe themselves as Christians, are willing to acknowledge the cultural benefits of Christian societies. Vanity Fair's recent article [1] gives some flavour of the figures and movements involved, while viewing the phenomenon rather suspiciously through the magazine's progressive perspective on American conservative politics and its entanglement with religion. Russell Brand, J.D. Vance and Jordan Peterson are among the more recognisable names mentioned in this article.

Let’s start by separating clearly the two categories already touched on: those celebrities who have actually become Christians from those who remain non-Christian or only culturally attached to Christianity. Both categories are addressed and indeed partially represented in an UnHerd discussion between Richard Dawkins and Ayaan Hirsi Ali, the Somali-born Dutch-American writer and activist who has been primarily known as a critic of Islam and until recently, a militant atheist [2]. Dawkins in the discussion occasionally says some nice things about Christianity (and has elsewhere apparently called himself a ‘cultural Christian’ [3]) but is extremely clear that he thinks Christianity both false and dangerous, even if less dangerous than Islam. Hirsi Ali on the other hand seems to have had a genuine albeit still incomplete conversion to Christianity:

I find that Christianity is actually obsessed with love. That is in the figure of the teaching of Christ….The message of Christianity I get is that it’s a message of love. It’s a message of redemption. And it’s a story of renewal and rebirth. So, Jesus dying and rising again for me symbolises that story. In a small way I felt I had died and I was born. That story of redemption, and rebirth, I think makes Christianity actually a very, very powerful story for the human condition and human existence. The pain of suffering, but also our internal recognition of what you call sin.

Dawkins, despite suspicions that it is less a conversion and more of a development of her opposition to Islam, seems finally to recognise its genuineness:

I came here prepared to persuade you Ayaan that you’re not a Christian. But I think you are a Christian. And I think Christianity is nonsense. You appear to be a theist, you appear to believe in some kind of higher power.

Compared to the complete teaching of the Catholic Church, Hirsi Ali’s explanation of her beliefs is clearly an inadequate form of Christianity. I’m not sure precisely what brand of Christianity she has adopted, but she seems quite clear she is still exploring it:

Ayaan Hirsi Ali : I won’t survive death. I don’t think you will survive death. I said that when Bertrand Russell said, ‘When we die, we shall rot’, that is true. But then what happens to the soul consciousness, etc. That again I can’t say.

Richard Dawkins: You think there is a soul that survives death?

Ayaan Hirsi Ali: Well, there is something that I did feel a connection to and it wasn’t a bodily connection. It was a connection through consciousness and mind and whether that’s going to outlast me or not, I don’t know. I don’t know about that.

But that incompleteness is no indication of a lack of sincerity. All of us struggle to live a fully Christian life, both in terms of belief and in terms of action and motivations. That reality is sometimes obscured by a rather Evangelical Protestant emphasis on the simplicity of the conversion experience: you either accept Jesus as your Lord and Saviour or you don’t. The Catholic analysis of conversion is more about a continuing process of improvement or divinisation: we are initiated into the body of Christ through the sacraments and, with our ‘yes’ to God’s grace, grow closer to him Ignoring the details of her denominational commitments, Hirsi Ali sounds like someone who would fit perfectly into an RCIA programme for exploring sacramental reception into the Church.

What then of the truly cultural Christians, who may well be sympathetic to the Church or like some of its political or aesthetic values, but remain clear that they are not Christian? A lot depends on the precise variety of cultural Christianity adopted. Dawkins -to the extent he is any sort of cultural Christian- seems limited to a liking for some Christian art and an acceptance that the Enlightenment grew out of (but away from) an historical Christian background. It is probably a symptom of how much cultural damage secularisation has done that such views are even worth noticing: that Christians did some good art and dominated intellectual life until very recently in the West should hardly be news. But others, who see genuine moral and political goods in Christianity even if they can’t accept the theological teachings behind them, seem to be a quite different position. If, for the sake of simplicity, we reduce the centre of Christianity to loving God and loving your neighbour, many cultural Christians seem to be in the position of rather liking the teachings about how to love your neighbour but being unable to accept the beliefs about God. As Niall Fergusson, Hirsi Ali’s husband and historian, declared:

[A]theism, particularly in its militant forms, is really a very dangerous metaphysical framework for a society. I know I can’t achieve religious faith…but I do think we should go to church….I’m a big believer that with the inherited wisdom of a two-millennia old religion, we’ve got a pretty good framework to work with. [3]

That’s not enough to get into the Church now, but it should be enough to begin an exploration which might eventually lead you into the Church.

Although there may be some reasons for hope in some aspects of this movement, any optimism needs to be tempered by the wider background of religious decline in the West. A predominantly American perspective is particularly misleading when applied to the Scottish religious landscape. In both in the US and Scotland, there has been a striking increase over recent years in those ‘having no religion’ (Scotland) or those who are ‘religiously unaffiliated’ (US) which shows no signs of tailing off in the knowable future. But even with this trend, the US still remains publicly religious in a way that has little similarity to Western Europe and, particularly, Scotland. For example, in the 2022 Scottish census, 51.1% of the population identified itself as having no religion, with only 38.8% identifying as some variety of Christian, including 13.3% as Catholic. Compare this with US figures from the 2023 PRRI Census of American Religion which showed 66% of Americans identifying as Christian, including 22% as Catholic, with only 27% as 'religiously unaffiliated' [4]. For ‘influencers’ primarily focused on the US market, religious branding is going to be part of a marketing mix. Few Scots, on the other hand, will grow rich by favouring traditional religion.

To sum up, I’m not at all sure that the phenomenon of celebrity conversion or celebrity interest in Christianity is going to have much effect on the process of secularisation particularly in Scotland. At best, it is possibly a symptom that the high tide of celebrity atheism has passed. It is, however, a reminder that ‘the inherited wisdom of a two-millenia old religion’ will always attract some people, perhaps especially intelligent, imaginative people. The Church needs to think both how it can present that wisdom so that more people can be interested in it, and then how to convert that interest into a genuine love of God and a willingness to embark on the process of drawing closer to God.

References:

1. Vanity Fair, 'Behind the Catholic Right’s Celebrity-Conversion Industrial Complex' (https://www.vanityfair.com/news/story/catholic-right-celebrity-conversion-industrial-complex archived here: https://archive.ph/RGry5 )

2. The God Debate https://unherd.com/watch-listen/the-god-debate/

3. Think. ‘The turning tide of intellectual atheism.’ https://thinktheology.co.uk/blog/article/the_turning_tide_of_intellectual_atheism

4. Scottish census figures https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/czddp0j488qov PRRI figures https://www.prri.org/research/census-2023-american-religion/

The month of October draw nears us with important Saints such as St Rule of the town of St Andrews to celebrate along with some interesting female Saints, such as St Tridunna with a wide area of veneration that includes Orkney, Caithness, Edinburgh and Forfarshire. She also has potential connections with St Andrews on the Fife coast and with Hexham in Northern England. Most importantly, October is the month of our beautiful Lady’s rosary, which is an excellent time to reacquaint or start afresh with Mary and her prayer.