A Deep and Strange Type of Strength

Why should a Scottish Catholic read Chaucer? Stephen Watt on the joys of the Canterbury Tales.

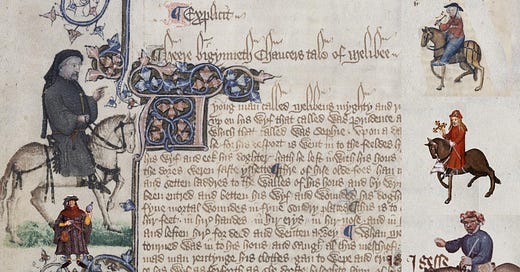

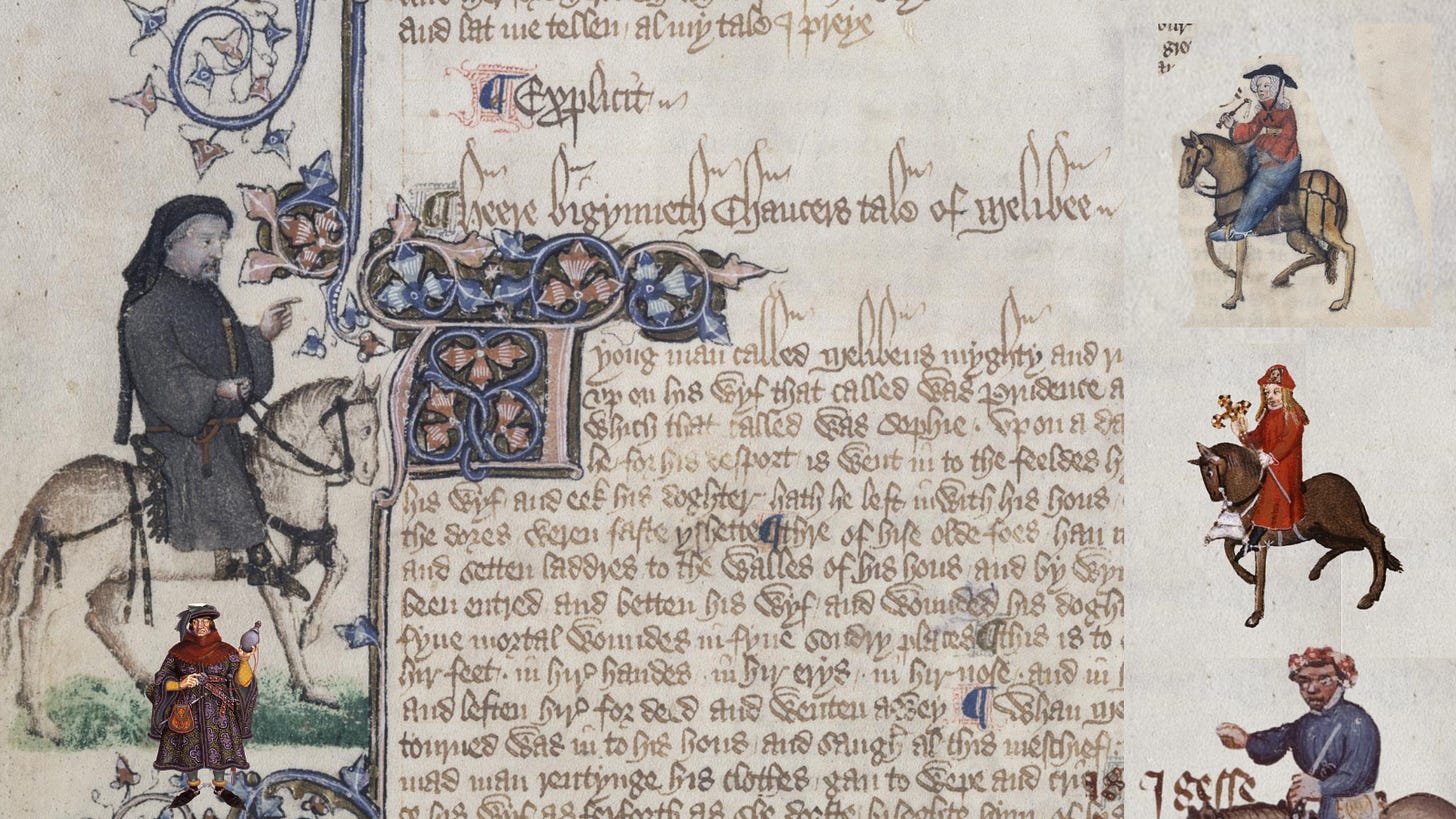

This upcoming month we are celebrating the Canterbury Tales. It may not be a subject that trips off the tongue when considering Catholicism in 21st Century Scotland, however the Tales are timeless and not only enjoyable, ask the same hard hitting and deeply affective questions we do today; as Catholics we can see in his work, as Dryden so famously said, ‘Gods plenty’. We will cover this subject into November as well but begin this week as the anniversary of Chaucers death was on the 25th October.

As part of our offering over the next month we have a Chaucer expert writing for us, Paul Strohm; Proffessor Emeritus of the Humanties at Columbia University and previously the J.R.R Tolkien Professor of English Language and Literature at the University of Oxford. He is the author of many books and scholarly articles on the man himself and his works.

Many people tried to spend the UK COVID lockdowns in positive ways. I made all sorts of resolutions, but the only one I really kept was to read The Canterbury Tales for the first time. You’ll see in detail what I made of it below, but I’d strongly recommend Scottish Catholics to try and engage with Chaucer as a way of getting to grips with what lived Catholicism was like in Britain before the Reformation: a complex mixture of different personalities, different vocations, sex and the sacred, and all wonderfully vibrant and human. And nothing like the modern caricature of a Christian society.

I’m not sure if this was the best method, but I ‘read’ The Canterbury Tales generally by listening to an audio version which, although it varied from reader to reader, tended to keep to the original Middle English text, but only lightly followed the original pronunciation. I followed the reading in the Middle English text and then re-read it in modern English, concentrating on those bits I didn’t really understand in the original text.

So, first of all, congratulate me! I feel it was a bit of an achievement, which is one of the worries I’m going to address in this piece: Why did I feel it was a bit of a chore, with a sense that I was constantly looking over my shoulder and expecting applause for that chore?

Chaucer has lain in the background of my life as a classic of English literature. (That’s part of what classics are: they lie around in the landscape, whether or not we actually visit them very much. The status of classic marks a cultural work as worthwhile, even if we yet aren’t quite ready to appreciate it.) But two things, besides the competitive, cultural target setting of the COVID period, drove me on finally to read him. First, having become a Catholic about twenty years ago, it’s hard to avoid the thought that the Middle Ages need to be treated seriously as the last time Britain had a coherent Catholic culture. Chaucer is one way into that thought, and, having read much of Chesterton including Chesterton on Chaucer a good few years ago, Chaucer also seemed likely to be a particularly Catholic form of that encounter. Second, having developed an interest in mediaeval theology and philosophy over the years, I constantly struggled to get inside the mediaeval head (if such a thing exists). I remember in particular one student asking me to recommend one book that would help her do this: I floundered, thought about suggesting the (as yet unread) Chaucer, but thought better of it. I would like to do better the next time I encounter a similar question.

So here I am: three years or so later and finally Chaucered. It went pretty well. I enjoyed quite a lot of it in a fairly uncomplicated way. I enjoyed that lurching from high thought to low humour. But it was an effort and now, afterwards, I keep wondering whether I did really enjoy it and whether I would really recommend this experience to someone else.

I’m going to try and answer those questions by starting with the question: Why read old books at all? Chaucer’s Middle English is certainly more of a barrier than Shakespeare’s Early Modern English, but manageable in a way that Beowulf’s Old English is not. But there is going to be some linguistic effort involved if we are to tackle Chaucer. Is it worth it? Let’s say that we read old books because of a complex blend of the familiar and the foreign: the oldness of a book in terms of its culture and its language forces us beyond what surrounds us and confronts us with possibilities of humanity that surprise or even shock us. We need that shock because otherwise we too easily sit within the fantasies of the modern entertainment world: we all think like this, and only monsters like them do not. But beyond this needful shock of the unfamiliar, there is the echo of familiarity, even that familiarity of half-forgotten and half-glimpsed beginnings which makes works like Chaucer’s necessary to us in a way that, say, Chinese literature of a millennium ago, however worthwhile, normally is not. During the Second World War, the high literature of Chaucer and Shakespeare was familiar enough to cinemagoers to allow the viewers of Powell and Pressburger’s A Canterbury Tale or Olivier’s Henry V to identify them at least as symbols of something that was essential to their lives and something worth fighting for. For a conservative mind that sees a culture as an organic growth, in Edmund Burke’s words, ‘a contract between the dead, the living and those yet to be born’, or in Chesterton’s, ‘the democracy of the dead’, to cut oneself off from a cultural root such as Chaucer is to cut oneself off from fully understanding even more recent generations such as that of the Second World War and, indeed, ourselves.

For Catholics, the case for effort in overcoming the strangeness of Chaucer is even more pressing. For us, Chaucer has sometimes been deliberately used to block our own self-understanding: to peel away those deceits about him and his times is to peel away barriers to our own selves. For the Protestant and then secularised interpretation of Chaucer is that Chaucer is immersed in the Middle Ages and thus in darkness. He lives in a theocracy and hence we can explain the longueurs of his ‘Parson’s Sermon’. (So why read him?) Or at best he represents the first stirrings of the rejection of repressive, celibate, priestly, Latin culture, and its replacement by Protestantism or, better still, our Enlightened freedom. (So why read the accounts of an old battle? It’s done.) But here’s an alternative view. As Chesterton puts it:

It was of the very life of the ancient civilization, Pagan as well as Christian, from which medievalism drew its deep and strange type of strength, that it was rooted in very varied realities; that it had made a cosmos out of a chaos of experiences; that it knew what was positive and could yet allow for what was really relative; that its Christ was shared by God and Man; that its government was shared by God and Caesar: that its philosophers made a bridge between faith and reason, between freedom and fatalism; and that its moralists warned men alike against presumption and despair. Only by understanding all that ten times complicated sort of complication, can we see how Geoffrey Chaucer could find life so simple.

For Chesterton, the essence of mediaeval culture is that it finds a balance between apparently competing realities. Among our twenty-first century obsessions, we might note especially a balance between sex and religion, and between seriousness and humour. It would be rather bold to claim that Chaucer (or mediaeval Christendom in general) resolved these tensions, but it is clear even from a cursory reading of the texts that he lived with them in a way that is profoundly different from how we attempt to. And we often read literature to find a fresh landscape within which a different life and sensibility can be glimpsed rather than to find solutions.

Reading Chaucer isn’t always going to be easy and will require effort, as is proper with a classic, to live with it. But there is a desperate need to escape from the modern entertainment monoculture and that’s inevitably going to discomfort us. Indeed, isn’t it typically modern to expect entertainment (rather than studying) to be easy? Reading Chaucer is something I’d recommend as a lifetime’s adventure. I think it’s probably going to repay the effort and enough readers over the centuries have agreed with me to make that gambling of effort a plausible bet. If I were to attempt a perhaps overly neat ending, reading The Canterbury Tales is itself a sort of pilgrimage, as though:

The holy blissful martyr for to seek

That them hath holpen when that they were sick.

By Stephen Watt

Saints of the week:

Please go to www.maryswell.net/novembersaints for all our local Scottish saints.